The following comes from the April 2019 issue of Truck Parts & Service. To read a digital version of the magazine, please click the image below.

While it won’t go down as the most famous printing invention ever — Johannes Gutenberg’s creation seems likely to hold that title in perpetuity — few technologies in recent decades have been as developmentally groundbreaking as 3D printing.

Introduced in the 1980s and greatly refined over the last decade, 3D printing is a production method using advanced computer technology in which the composition of a material is altered then reshaped and molded to create a three-dimensional object.

Also known as additive manufacturing, 3D printing is a production method with strengths and weaknesses. It’s not a great way to make everything but it is a great way to make specific products ill-suited for mass production.

As it gains traction within trucking’s manufacturer community, it is important for aftermarket businesses to understand why suppliers are turning to the solution. Distributors are going to be expected to sell 3D-printed parts in the future.

Best to understand the technology now than wait and be blindsided by it in a few years.

Understanding 3D printing

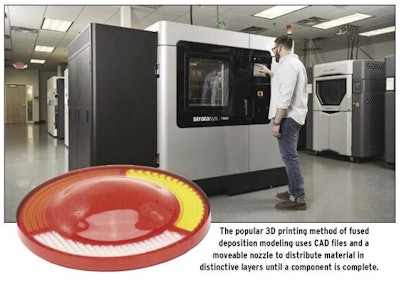

The most popular 3D printing method in use today is fused deposition modeling (FDM). The printing technique uses computer-aided design (CAD) files and a moveable nozzle to distribute material in distinctive layers until a component is complete. FDM’s popularity and acceptance is rooted in its accuracy and its simplicity. Using primarily thermal plastics and polymers, FDM enables users to develop complex objects in a single print.

While FDM is the most identified and recognized 3D printing technique, other processes exist to print objects from resins, metals and even organic tissue, says Matt Havekost, vice president of sales — additive technologies, for industrial printing supplier AdvancedTek.

“Most of what you’ll see in traditional manufacturing is thermal plastics, resins and metals, but materials like concretes, or even human tissue, are being developed,” he says.

“I think a big barrier when 3D printing first hit the scene was the type of commodities that could be utilized. Everyone thought it was just plastics. That’s not the case at all,” adds Eric Starks, chairman and CEO, FTR Transportation Intelligence.

“If you can manufacture with it, you can probably print with it,” he says.

As it evolves, the 3D printing industry also is developing more sophisticated procedures to support specialized demands from industries such as aerospace, energy and healthcare.

“We like to use it as a proof of concept tool,” Bendix Vice President of Engineering Research and Development Richard Beyer says of his company’s 3D printer. “Sometimes when you are in the development of a complex product there may be issues from a machining standpoint you may not see in a CAD environment. We will print a prototype to test the concept before we decide to do a cast.”

It’s the same story at Minimizer, which purchased its 3D printer from AdvancedTek in 2012, says Vice President Jim Richards.

“For us it is 100 percent a prototype and engineering tool,” he says. “We’ve used it for some jigs and fixtures but never for sellable parts.”

Similar to Bendix, Richards says Minimizer values the printer because of the speed in which it enables the company’s engineers to test their designs. While 3D printing itself can be a slow process, the time Minimizer saves by not creating molds for each new idea more than makes the technology worthwhile, he says.

Havekost says these uses fall into the first two of four common buckets of 3D printing usage and adoption: prototyping, function testing, tooling and end-use parts. He says as a manufacturer becomes more confident in a 3D printer’s performance, it will start using the printer closer to the final production stage.

Even manufacturers who purchase a 3D printer with the goal of printing retail parts rarely use the tool in that manner immediately. Familiarizing oneself with the technology is important.

Havekost references two other AdvancedTek customers who recently created strategic departments within their organizations to better use their 3D printers. He says the companies had used the printers for traditional R&D and testing for more than a decade before identifying new methods to use the technology moving forward.

“It’s all about trying to find out how you can leverage it,” Havekost says. “3D printing is not a magic bullet. In most cases it is a complement to traditional production methods.”

Starks agrees. He believes the prevalence of 3D printers is unquestionably on the rise in the trucking industry but he stops short of designating the technology the future of mass production. Starks says the future of 3D printing in trucking is on the margins, such as specialized componentry for new vehicles and legacy aftermarket parts that no longer require the volume necessary to support a conventional manufacturing line.

That’s how it is being used at Daimler Trucks North America (DTNA), says Angela Timmen, manager, interior/exterior cab and major components. Timmen says the OEM started using the technology about a year ago to “solve the problem of long-lead time parts and parts where the supplier set could not find tooling to manufacture the parts.”

Thus far DTNA’s 3D printers have focused on plastic and composite components in non-safety relevant positions, though Timmen says as the technology improves, so too does DTNA’s interest in it. She says customer response to DTNA’s first 3D-printed parts was “very positive.”

Where 3D printing fits in the future of trucking

DTNA’s end-use parts success remains an outlier in the trucking market. Adoption of 3D printers is on the rise but remains low overall. Suppliers cite the cost of the equipment, available printing materials and issues with part complexity as key barriers to widespread adoption.

“I think like with a lot of new technology that hits our market, there is hype and then there is reality,” says Beyer. “I think we are still a little bit in the hype stage with [3D printing]. There is a reality where it does make sense for us to print parts, but I think it is going to be a small number of parts for very specific applications.”

Midwest Truck & Auto Parts researched 3D printers in 2017 but decided the acquisition cost at the time was too high to justify the investment, says Director of Marketing Steve Filipiak. Like the manufacturers previously mentioned, Filipiak says Midwest Truck & Auto Parts sees potential for 3D printing within the aftermarket. He says the company intends to investigate the technology again in the near future but felt in 2017 the “price point was not feasible for how we wanted to use it.”

Morales says the only fee to members is the cost of the materials.

But Starks adds it is important to note like any new technology, the costs of 3D printing are falling, not rising. He says long-term adoption of 3D printing in the trucking industry will be dependent on the materials used, not price.

Beyer agrees and references the hundreds of safety-related parts in the Bendix product portfolio. He says Bendix performs intricate validation tests on the materials used in all those components before they enter production. For Bendix to turn to 3D printing for any of those components — even at low volumes — Beyer says similar performance tests would be required.

“What happens if you print a safety product and then it doesn’t work right?” he says.

Fortunately, the additive manufacturing industry is working to solve these issues. Material capabilities and performance continue to increase. Havekost says he has many industrial customers currently printing with stainless steel, while Starks notes the aerospace industry is heavily relying on titanium.

The technology is coming, Starks says. When it hits is only a matter of time.

“For some components, I think this is absolutely the future,” he says. “There will be a point where if you want it, it is going to be additive manufactured.”