How you can best navigate changing global trade:

- Politics is back in the boardroom in a big way as policies shift away from globalized supply chains and labor pools.

- The United States, with imports making up just 11% of GDP, is less exposed than many other countries, but the commercial vehicle industry faces more scrutiny than others.

- More bilateral deals will pepper the global trading landscape, meaning more uncertainty for companies.

- Adaptability, flexibility and resiliency are critical to success.

For the last 40 or so years, Jeffrey Crane, partner with Bain & Company says, politics was mostly outside of the boardroom. It was generally assumed globalization, whether it was goods or labor, was spreading and would only get freer.

That time is over, he told attendees at MEMA’s Commercial Vehicle Conference on Tuesday.

“These are not things that can be ignored,” Crane says. And one thing that’s certain, “You can’t wait for certainty. Certainty is not around the corner here.”

Trending Inflections

Crane outlined four trends that shaped the world in recent years: Globalization; easy to get capital; a growing labor pool and continued urbanization. Now, he says, nations around the world, not just the U.S., are looking more to their own interests. Capital is becoming more difficult and expensive to get. Human labor is being replaced by automation and AI, and, for the first time in more than 200 years, more people are moving out of cities.

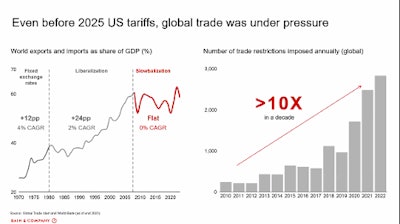

Even before the volatility of this year, Crane says globalization was under pressure.

[RELATED: Parts operations taking ‘wait and see’ approach to tariffs]

“This did not start with [President] Donald Trump. It will not end with Donald Trump,” Crane says. Countries leaned on China, in particular, including on steel and battery electric vehicles (BEVs). He pointed out other countries’ tariffs against China, including Canada (2024), South Korea (2025) and the European Union (2024).

U.S. imports and exports, a 35,000-ft. view

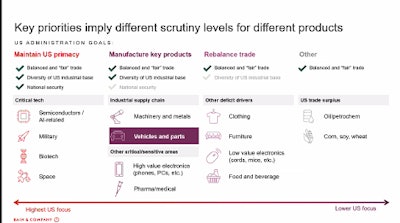

The U.S. is the largest importer in the world, he says, but it’s still only about 11% of the U.S. gross domestic product. It has three policy objectives: a restored diversity of the American industrial base, balanced and fair trade, and increased national security.

Vehicles and parts are intertwined with national security goals, Crane says, including the very obvious connections to the military system, but also because of its importance to commerce. Crane says the extra scrutiny isn’t necessarily bad things. For instance, he says, suppliers should be a little less worried about Chinese competition, as he can’t see the government allowing those companies to infiltrate too much of the space.

“The U.S. trade in goods and services is lower than basically any other country in the world,” he says, with a large domestic economy centered on services, which are less exposed to global trade. But because the U.S. is the largest importer, any reduction in the trade deficit will create bigger issues for exporters, such as China and Germany.

Crain says Bain remains bullish on the U.S. in the long term. China, he says, and Europe both have structural difficulties. And while the short-term may be hard, medium- and long-term forecasts look good for the commercial vehicle industry. Any increase in domestic production in the U.S., he says, is ultimately good for on-highway transportation.

“But there’s no shortage of challenges in the next 12-24 months,” Crane says.

Long-term deals on deck

Crane says Baine sees Mexico and Canada trade deals are likely. A strong U.S. supply chain “requires Mexico,” and both countries are reliant on the U.S. as a trading partner. Plus, a North American bloc would be more powerful than the U.S. on its own.

“There’s just not going to be certainty soon, but we feel pretty good Mexico and Canada have to get something done,” he says, perhaps on the lines of another U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), negotiated during the first Trump administration.

[RELATED: It’s hard to find good news in an economic forecast these days]

Much of the requirements from Mexico are in the automotive industry. About 80% of the $918 billion U.S. trade deficit with Mexico comes from automotive, and there’s no guarantee USMCA exemptions would stay around.

“This is a risk factor as you think about your supply chains in Mexico,” he says.

Elsewhere, Crane says there’s no reset button to restore the old world order. No successor to Trump, no matter the political party, will restore faith in global free trade. Instead, Crane says, countries around the world will be more protectionist, especially with their industrial goods.

“There is a broader movement that is going to lead to a more fractured set of world trade relationships,” he says.

What can companies do?

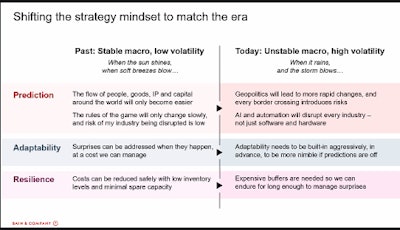

Crane says all companies make decisions based on predictions. But with more chaos in the marketplace, companies will need to account for that as they craft those predictions.

“You have to come up with your predictions and acknowledge there’s a very good chance that you’re wrong,” he says. “Think really hard about what happens if you’re wrong.”

Adaptability and resilience should be figured into any plans, especially when it comes to supply chain investments, including building or expanding factories. Keep in mind, Crane says, these are both expensive concepts.

“Almost no company in the world can afford as much resilience as it wants to have,” he says, but it’s something every company will need. Without it, companies are paralyzed, waiting for firmer footing before moving ahead.

Thinking geopolitically again is a tough shift for companies, but it’s one leaders will need to factor in to forecasting from here on out. Crane advised leaders to be clear with their teams about why they’re making certain decisions and make plans for when the bets are wrong.

“If you wait until certainty,” he warns, “you will be too late and lose your competitive edge.”