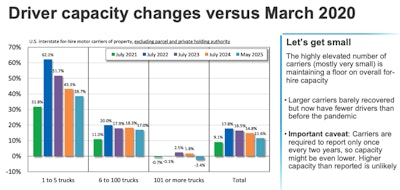

Economic uncertainty, coupled with higher insurance costs, flat rates, and changing policies from Washington, D.C., may finally come for the burgeoning number of small carriers that proliferated during the pandemic.

"We've had a very resilient group of very small carriers," Vise said in a Thursday State of Freight webinar. But there are threats, such as continuing low freight rates, plodding volumes and a sluggish, uncertainty-plagued macroeconomic outlook.

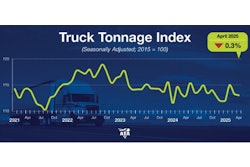

Vise says analysts at FTR don't see any inflection upward in dry van spot rates and refrigerated spot rates remain weak, with flatbed metrics remaining a bright in an otherwise pretty bleak spot outlook. Loadings are also not very strong, he says, and contract rates will likely remain weak.

If overall rates remain low, he says, there will most likely be a contraction in capacity as these formerly resilient small carriers tumble.

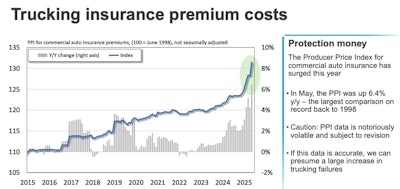

One of the rising costs Vise is watching is the cost of insurance. FTR tracks the cost of commercial auto insurance, which Vise says is the closest the company can get to over-the-road trucking. Prices skyrocketed in May, up 6.4% year-over-year, which is the largest comparison increase on record. Even if that number is revised downward later, as the volatile index tends to be, it's still a strong increase.

"If this data is accurate, we're going to start losing a lot of small carriers unless we see an increase in spot rates or freight activity," Vise says.

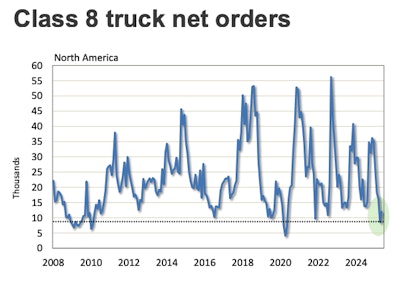

Higher costs and flat rates also means carriers of all sizes aren't buying trucks. April saw the lowest level of Class 8 net orders since the pandemic lockdowns.

"We have a lot of uncertainty," Vise said. "We don't know exactly what the EPA regulations are going to be or how they're going to be enforced. We do presume there won't be the same pre-buy pressure that we were expecting under the Biden administration."

Fewer new trucks now could spell tighter capacity down the road, Vise says. Maybe not this year, but as the economy is expected to improve in 2026 and 2027, he says, carriers may find themselves without enough trucks to service a recovery.

Compounding the issue is a federal investigation into the national security implications of imports of medium- and heavy-duty trucks and parts. About 40% of Class 8 trucks bought in the U.S. are made in Mexico. A comment period on the investigation ended May 16. More than 3,300 comments were filed and around 100 have been made public so far.

"One of the interesting things I found in the Federal Register notice of this was the comment that truck prices might be artificially suppressed due to unfair foreign competition," Vise says. "I would ask all the carriers if they are paying too little for their trucks."

The American Trucking Associations, in their comment, pointed out if there was a presumed 25% tariff on trucks built in Mexico added to the price of a new truck, along with the 12% federal excise tax, the average price of a new Class 8 truck would jump from $170,000 to $224,000.

"There is likely to be a response by moving some production to the U.S., but that will almost certainly have some cost implications," Vise says.

Another federal policy that may have implications for trucking capacity is the enforcement of English proficiency rules. On June 25, failure to demonstrate adequate English skills will become an out-of-service violation, except in commercial border zones, a factor that dramatically changes overall numbers, Vise says.

While FTR's analysis shows violations affected 17,855 unique trucks — "not enough to move the market" — the policy may drive some drivers out of the market completely or, if it becomes a universal out-of-service violation, a service failure issue. It could also become a tort liability problem if a driver with marginal English skills is involved in a crash, Vise says, which may quickly become an overbearing risk for some of the smaller carriers in the market.

For the near term, Vise says, capacity appears to be stable, so long as the smaller carriers can keep on rolling and the freight market, diesel prices and other costs remain somewhat as expected.

"We are still unsure, but it does feel like the most dramatic potential hits to the market — which by far was going to be the 145% tariff on China — that risk has gone away," he says. "As we look at our outlook, the kind of severe downturn that might also take a lot of capacity seems to have greatly dissipated as a risk."