Jim Hinton pauses. He has to think. The Summit Truck Group service trainer has been working so hard for so long to recruit new technicians into his company’s 31-location dealer network that he can’t even remember the last time Summit’s service centers didn’t have a “Help Wanted” sign in their front windows. He guesses the signs have been posted since 2010.

As for job openings, Hinton says Summit has been aware of a shrinking technician talent pool across the Southeast since at least 2006.

On the other side of the country, Ray Schmidt isn’t as certain on the timeline, but echoes Hinton’s sentiments when he says technician employment has been the top priority for his company’s service department for several years.

“Hiring and recruiting techs is a weekly conversation for us,” says Schmidt, service manager, McCoy Freightliner, a company with 63 technicians across three locations in Portland and Salem, Ore. “None of our shops are operating at full capacity … and finding quality technicians to bring in is getting harder.”

Hinton corroborates Schmidt’s account. He estimates Summit has at least 30 technician openings across its network. It’s a number he hates to think about but he is unfortunately learning to live with it. “I don’t see an end in sight,” he says.

The worst part is he’s right. Trucking’s technician shortage is real, and it’s intensifying.

Though Hinton pegs 2006 as the year Summit first identified the shortage, the trucking industry’s path to today’s unfortunate position is the result of a number of independently occurring factors.

Navistar’s John Pfennig Jr., director of training delivery and recruitment, says one contributing aspect of today’s shortage is rooted in the past. The trucking industry has been led by one generation for decades and that generation is aging out of the workforce.

There aren’t enough working Baby Boomers to cover trucking’s job openings anymore.

“I think for a long time no one ever measured the generational population of the technicians in our industry,” says Pfennig. “I don’t think we ever realized how many of our technicians were Baby Boomers until they started retiring. That kind of caught us off guard.”

TA/Petro Director of Technical Service Homer Hogg subscribes to this theory. Hogg entered the trucking industry as a service technician in the early 1980s when tech jobs, and applicants, were plentiful. He says many of his first colleagues were close to him in age and, as he advanced up the corporate ladder, he watched as his contemporaries stepped into his previous positions or rose with him.

TAG Truck Center has built a technical training center at its Memphis, Tenn., location to help onboard new technicians for its entire dealer group.

TAG Truck Center has built a technical training center at its Memphis, Tenn., location to help onboard new technicians for its entire dealer group.Hogg says today’s shop floor population is much different. Boomer-aged veteran techs hold most management roles but the workforces they lead are increasingly Generation X and Millennials. And, unlike Hogg’s generation, which gravitated toward technical careers as a path toward a stable career, Hogg says new entrants to the workforce appear to view that career choice with ambivalence, at best. The fathers who powered trucking’s service channel for decades are retiring and their sons are uninterested in following in their footsteps.

“I think it is very clear that the generations we see coming into the business today are different from those of us who have been doing this for a while,” says Hogg.

Trucking also has become a victim of its own success. Freight activity and tonnage have grown progressively since the Great Recession. Medium- and heavy-duty truck populations are on the rise. Fleets and their customers are relying on trucks to move more goods than at any point in North American history.

But with that customer reliance also has come elevated customer expectations and a surge in consumer technology. Today’s economy is built on same-day, two-day and overnight shipping. Downtime has shifted from an unfortunate but accepted reality in trucking to becoming a legitimate dirty word.

Trucking is outgrowing its service channel.

“The economy is very good right now and I think that puts a lot of pressure on us as service providers,” says Charlie Nichols, general manager, TAG Truck Center — Calvert City, Ky. “We recognize that technicians are critical. Without them, the whole infrastructure of our economy kind of collapses.”

Service businesses throughout the industry have responded appropriately to this business growth, raising technician wages and investing in technology and training to improve technician productivity. Yet even with these investments, trucking’s technician shortage has swelled.

A December 2018 report by the TechForce Foundation states the heavy-duty diesel service business is expected to require more than 4,300 new technician positions this year. Coupled with a replacement demand projection of more than 25,000 positions (caused by retirements, employment changes, etc.), the TechForce Foundation says the trucking industry needs to hire nearly 30,000 heavy-duty truck techs in 2019.

United States Bureau of Labor Statistics’ numbers aren’t any better. The agency estimated earlier this decade there will be a 9.2 percent increase in the need for heavy-duty service technicians and an 8.6 percent increase in the need for truck and bus technicians and diesel engine specialists in 2022 from 2012 levels.

What was once a nuisance has become a four-alarm catastrophe.

How will the trucking industry solve this growing conundrum? OEMs, dealers and independent service providers actively hiring and recruiting technicians in the market say the shortage has become too big to ignore. But while those same professionals also believe no simple solution exists to swiftly solve the service channel’s biggest problem, they say the industry isn’t without options.

By better understanding how a career as a heavy-duty diesel truck technician is perceived within the trucking industry and by the general population, trucking’s service channel must identify recruitment and retention initiatives that will appeal to the demographic groups most likely to apply, accept and enjoy a career working as a technician.

“It’s time to understand the challenges facing [our] organizations and look into what is driving those challenges,” says Hogg. “Our labor pool is shrinking. We have to start looking beyond our normal hunting ground.”

Universal Technical Institute (UTI) and Navistar have partnered to offer a 14-week training program to UTI graduates who are interested in a career with the OEM’s dealer channel.

Universal Technical Institute (UTI) and Navistar have partnered to offer a 14-week training program to UTI graduates who are interested in a career with the OEM’s dealer channel.If there’s one consensus within trucking regarding technicians, it’s that the profession is poorly perceived by those outside the industry. The degrading “grease monkey” stigma that plagues the automotive service channel is doubly damaging in trucking, where the equipment is larger, heavier and often dirtier.

Schmidt says all too often when attending educational career fairs at high schools and technical schools as part of his recruiting responsibilities he will interact with a student or parent who never considered a tech job because “they think it’s dirty, low-pay work.

“It’s not like that at all,” he says. “If you’re working on a truck sometimes you can get dirty, sure, but it’s not like that all the time.”

“Being a diesel technician is not a sexy job. I get that. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t a good job,” says John Devany, general manager, Betts Truck Parts & Service. “The perception that what we do is big and scary is wrong.”

Devany says the reality is quite the opposite. Betts Truck Parts & Service makes significant investments each year in diagnostic equipment and computer-based service tools to be able to maintain heavy vehicles that become more technologically advanced with each passing year.

“A lot of kids today are growing up on tablets and computers and that’s our future,” says Devany. “What used to be about tribal knowledge is now becoming more of a white-glove environment.”

“People fixate on ‘techs get dirty’ and they do, but the job is so much more than that,” says Ian Johnston, vice president, operations and marketing, Harman Heavy Vehicle Specialists. “There is a ton of problem solving and critical thinking as well; it is becoming a far more tech-oriented job than it used to be.”

“We stopped saying mechanic for a reason,” adds Hinton.

The contemporary high school experience isn’t doing vocational careers any favors either, says Nichols. TAG Truck Center has a partnership with a local community college in which high school graduates can enroll in the school’s heavy truck program, receive financial support and real-world experience with TAG while in school and then have a job waiting for them when they complete the program in two years.

Nichols says the success rate of hiring students who enter the program is great. The challenge is getting them to sign up in the first place. He says too often his pitch for the program is met with apprehension from high school administrators, counselors and parents.

“There is a very big misconception in our country that every kid needs to go to a four-year college,” he says. “I don’t believe that’s the case. A four-year school is not the holy grail for everybody.”

Russ Dunnington knows this all too well. As diesel instructor and department chair at Portland Community College (PCC), Dunnington says he visits high schools to recruit potential students to his program multiple times per month. Dunnington’s program, which has partnerships with McCoy Freightliner, Daimler Trucks North America and other area service shops, has an incredible graduation and placement rate for its students.

But PCC’s success doesn’t always translate to its audience. Dunnington says each school visit yields one new PCC applicant, on average, and his program remains frustratingly under capacity.

“I get emails and calls from [service providers] every day begging me for students [to hire],” he says. “I only have so many.”

Those in the service channel add the parental dream to send one’s child to college is admirable, but college is more than private institutions and land grant universities. Vocational programs like the one at PCC offer students a path to an associate degree and more relevant professional experience and earning potential than many bachelor’s degrees.

That latter point is another one the trucking industry needs to better publicize, says Nichols. The heavy-duty diesel technician space is well-funded. Good techs stand to earn a good living.

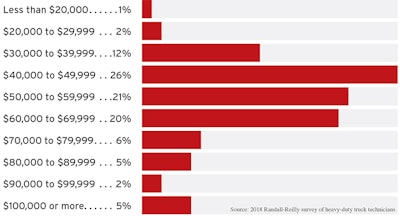

According to a 2018 survey of technicians in four industries (heavy truck, agriculture, construction and automotive) by Randall-Reilly, publisher of Truck Parts & Service, nearly 40 percent of heavy-duty truck technicians reported earning at least $60,000 per year. Nearly half of those same responders indicated earning more than $70,000 annually.

Additionally, during a speech at the 2019 American Truck Dealers (ATD) Show, ATD Chairwoman Jodie Teuton, vice president, Kenworth of Louisiana, noted the average truck technician salary at a dealership in 2018 was $61,000.

Says Nichols, “There are so many kids today who graduate from college and can’t get a job. You see them working in retail for not much money at all. They could be working for us making $50,000 to $70,000 a year plus benefits but they have no idea we pay like that.”

Randall-Reilly’s survey supported Nichols’ claim, as an overwhelming number of truck technician responders stated they receive health insurance (92 percent), paid holiday leave (83 percent) and 401K and/or IRA opportunities (83 percent) through their employers.

Meritor has created a technical training team to traverse North America and educate technicians and parts professionals on its components and maintenance requirements.

Meritor has created a technical training team to traverse North America and educate technicians and parts professionals on its components and maintenance requirements.That earning and benefits potential is something Meritor tries to bring to the forefront when interacting with young people through its partnership with Skills USA, says Peter Adair, technical training manager. The commercial vehicle supplier has supported Skills USA’s heavy truck technician education program for years through volunteer assistance and financial support.

Adair says students he works with are eager to learn about Meritor’s online curriculum and virtual educational library but adds when the topic of compensation comes up is when heads really start to turn.

“Maybe I need to be a technician again,” he jokes.

That’s another part of the issue, says Hinton. The trucking industry is filled with white-collar professionals who started their careers in a service bay. The lure of new opportunities and leadership roles moved them up the corporate ladder, but the roles and salaries they exited still remain. In time so too will their current roles. Trucking’s employment shortage is not limited solely to service bays.

Unfortunately, those career advancement opportunities are another source of employer-to-employee disconnect.

Only 29 percent of heavy truck technicians (and 28 percent of all technicians) answered they have a “clear career path at my current employer,” according to Randall-Reilly’s survey question regarding career advancement potential. Conversely, 24 percent of truck techs said a career path exists but has not been established by their current employer and another 20 percent answered that “someone would need to leave or retire for me to advance.”

Those already fighting the technician shortage say these misconceptions are just another hurdle the industry needs to clear. A national movement supported by trade organizations and/or the OEM community seems the most likely effort to drive real change, but at this time no program exists. As such, those in the service channel say they will continue doing what they can individually to create awareness and promote the career opportunities found in their marketplace.

“We do a good job when we’re presenting our case to high school students and their parents. I think those conversations can still be sort of eye opening to them,” Schmidt says. “But the big picture is we don’t do that as well as an industry.”

Johnston agrees. “At the grassroots and local levels, we still have that ability to develop relationships with students and vocational schools to begin to change the perception of these careers,” he says.