FTR’s experts, looking ahead to 2024 in a State of Freight webinar on Thursday, set a scene of continued uncertainty in the wake of the pandemic.

Jonathan Starks, FTR CEO, started off by setting the scene of what looks like a return to pre-pandemic normal. Manufacturing output is flat, hovering near or just below 2018-2019 levels with very little change in the last year. There’s not a lot of downside risk there, Starks says, but not a lot of upside potential, either.

[RELATED: Truck orders slip a bit but mostly strong in October]

Consumer spending on goods (just above long-term averages) and services (just below) are also fairly flat, Starks says. “We’ve actually been growing in goods spending, but just about 1, 1.5% when, historically, we’ve been growing about 3.5%, reducing the demand for transportation,” he says.

[RELATED: Truck tonnage slips again in September]

Household cash reserves are continuing to dive as pandemic-related stimulus accumulations dry up, and automotive sales are still below their pre-pandemic levels. Housing construction shows single-family home construction continuing to fall, but multi-family units growing, as it has done since the end of the Great Recession.

Economy expert Bill Witte says even recovering from unprecedented events is, well, unprecedented. And that wreaks havoc with traditional theories and models.

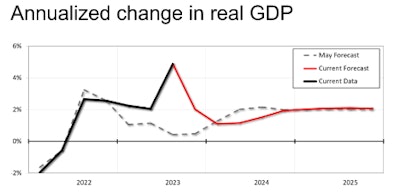

Third quarter gross domestic product (GDP) was double what it had been, something Witte calls a “significant” jump and bucking his and other economists’ forecasts.

“Third quarter data was way out of line, much stronger than we expected,” Witte says.

That includes not only GDP, but also employment numbers, coming in more weak that what transpired.

Witte does see the strong Q3 numbers as an aberration and expects the economy to return to a pattern of slow decline, though nothing approaching a recession.

[RELATED: FTR delivers weak peak season outlook]

“There’s certainly not an indication of an economy where the bottom is falling out,” Witte says.

Inflation will continue to drop, Witte says, with goods already near a 0% inflation. Services still has work to do and continues to prop up the inflation numbers across the board.

Where the inflation rates will go is beyond Witte’s modeling, he says.

“They don’t fit the data terribly well,” Witte says, undermining his confidence in any future forecasting of inflation rates, other than continued disinflation barring unforeseen circumstances such as snarled supply chains.

Uncertainty is also foiling modeling in the labor market. Witte says there was cheering a few weeks ago when the federal government announced the increase in the labor force slowed down in October, with demand for workers continuing to outstrip supply.

However, Witte says the problem isn’t with demand, it’s with supply.

“You can’t hire workers that aren’t there,” Witte says.

And the data for the supply side of the labor market isn’t very promising.

First of all, Witte says, it’s difficult to get a good picture of the labor supply. The surveys that generate the government’s numbers have their own problems, and Witte doesn’t have confidence that the available numbers are representative of the real picture.

Still and all, what the numbers show is sobering.

“The forecast assumes that the increases (in the labor force) have run their course,” Witte says. “Underlying demographics are going to assert themselves.”

The underlying demographics mean that the labor pool is declining as the Baby Boomers continue to retire and leave the labor supply. The last part of the Baby Boom will be 66 in 2030, Witte says, and until then, the demographics is going to continue to be negative.

Household savings continues to drop, Witte says, as pandemic-era payments dry up. How student loan repayments and reduced child care subsidies could dip into consumer saving and spending, but the effects of both remain to be seen.

Higher interest rates aren’t affecting spending and savings so much yet, Witte says, unless you have assets that are now earning more money than they did during years of rock-bottom rates. Where interest rates are really coming into play, he says, is in business investment.