Predicting the adoption curve for alternative powertrains in the immediate future has become a point of emphasis for truck makers and industry research experts.

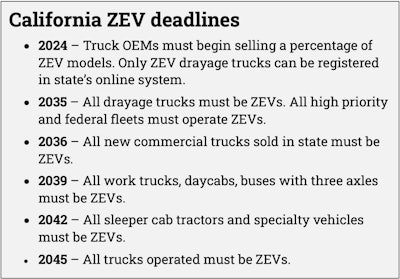

California will begin requiring the sale of truck and bus zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs) next year, with manufacturers only allowed to sell ZEVs by 2036. Other states have announced plans to follow California’s lead, and the United States also has committed to a global Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) to reach 30% ZEV truck and bus sales by the end of this decade and 100% ZEV by 2040.

But with current commercial ZEV sales hovering in the range of hundreds of units by weight class per year, truck buyers are showing little interest supporting these sales mandates.

Increasing alternative powertrain and ZEV adoption to meet state and federal goals will not come organically. Administrators will be forced to enact rules requiring truck owners to use this equipment, or the current barriers slowing adoption will need to be removed.

Manufacturers believe both are likely.

Regulations are already in development. California’s Advanced Clean Fleets rule, officially published in April, will require trucking companies in the state to only operate ZEVs by 2045. The other states committed to California’s truck sales rules have not yet committed to this regulation, but still could. California represents 22% of the American truck market, so even in isolation the state’s rule is groundbreaking.

Forced to develop equipment to support these regulations, OEMs are hopeful as their alternative powertrain technologies improve, so too will industry demand.

Daimler Truck North America (DTNA) believes the transformation of North America’s commercial trucking fleet to alternative powertrains is “highly dependent on three factors: compelling and capable vehicles; a robust and publicly accessible charging network; and positive [total cost of ownership].”

OEMs believe charging is the biggest sticking point. There is a full portfolio of medium- and heavy-duty battery electric vehicles available today from legacy and new manufacturers. TCO concerns thus far are neutralized by purchasing incentives and full-service leasing options — very few fleets nationwide have purchased EVs without financial support.

[RELATED: Trucking is pondering a future without the diesel engine. Why?]

Charging, however, remains a challenge.

“Charging access must be ubiquitous and seamless in order for widespread adoption to occur,” states DTNA. “Most of the infrastructure currently available is specific to passenger cars, or light-duty vehicles. Future builds will need to put primacy on stations that are designed to accommodate medium- and heavy-duty vehicles, as when you start with a commercial vehicle design (i.e., pull through stations, ample space for ingress and egress), you can also accommodate light-duty vehicles, but the converse is not true.”

“I think if you’re a customer considering an EV you probably need to be having conversions with your electricity provider before you’re talking to us,” adds Mack’s Scott Barraclough, senior product manager of e-Mobility. “We need to sustain the incentives programs we have, perhaps broaden them, to continue driving interest. But charging is the thing that slows us down the most.”

And charging isn’t a customer-exclusive issue. Dealers also will be expected to have charging capabilities on hand — even if only for service uses — and getting chargers working is no easy task no matter where you’re located.

[RELATED: Company unveils rendering of largest semi charging site in the U.S.]

Affinity Truck Centers President Kim Mesfin first contacted her utilities provider in central California to inquire about charging in 2020. Her facility has capacity to add DC fast chargers but, as of June 2023, Mesfin says she’s still waiting on her utility to improve its grid infrastructure. “I got a notice in May that I’m still nine months delayed,” she says.

Kriete Group is one of many truck dealers across North America that has proactively purchased EV chargers to support future customer interest and demand.Kriete Group

Kriete Group is one of many truck dealers across North America that has proactively purchased EV chargers to support future customer interest and demand.Kriete Group

Mesfin adds her dealership sold its first two EVs in early 2022; the fleet who bought them didn’t get its onsite charging set up until May 2023.

“This is happening and I believe it’s good that it’s happening. But this rollout is far from perfect,” she says. “Even if we have the trucks and the grants to pay for them, the trucks won’t go without chargers.”

“Infrastructure is still the biggest barrier to adoption,” adds Kenworth’s Sean Henebry, powertrain marketing manager. “Fast charging has long lead times for the chargers and the utility work needed to add power capacity. Hydrogen fuel production is still limited in volume with very few heavy-duty stations in existence.”

One positive for OEMs and their dealer partners investing into these technologies is more funding continues to become available for charging and fueling infrastructure. Governments understand converting America’s trucking fleet into ZEVs requires a transformation in how equipment is fueled and propelled. But until that transformation is well underway, it is unlikely ZEV adoption will rise at a rate much beyond regulatory minimums.

“I think the [customers] who can wait, will,” Mesfin says. “Why would they put their business through this if they don’t have to?”

Keep up with our special report on trucking's transition to cleaner trucks:

Part I: This isn't trucking's first fueling and propulsion revolution

Part II: Why are we doing this?

Part III: What constitutes as ‘alternative power’?

Part V: Performing an alternative power market analysis

Part VI: What it takes to install charging infrastructure

Part VII: Training on alternative powertrains vital to employee safety, business success

Part VIII: The challenges of building your best EV service bay

Part IX: Making the case: How to effectively sell alternative power

Part X: Safety in the Service Bay

Part XI: How electric trucks may transform dealer revenue streams