In my earlier article on supply chain, we noted a turn in the ocean freight side of things, at least in the Pacific. We saw container traffic has continued to grow, but the serious backlogs at ports were improving.

In this update I will discuss the domestic intermodal freight situation. Here, the outlook is more pessimistic with several 'wild cards' yet to be played.

What’s the situation at U.S. Ports?

The dual ports of Los Angeles/Long Beach have been poster children for supply chain problems. Problems unloading ships have been gradually decreasing, as some actual improvements have been made, and volumes dropped. A wild card is the negotiation of a new labor agreement for port workers. It’s anyone’s guess whether this will result in an agreeable settlement or a labor stoppage. The past agreement expired June 30, 2022, and so far both sides remain at the bargaining table.

Another wild card is the recent news that the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear an appeal on the California bill AB-5. This bill makes it much more difficult to classify truck drivers as independent contractors. While passed a few years ago, enforcement was halted pending the lawsuit. Industry experts expect this to reduce the overall number of drivers, while increasing labor costs for those who remain. Ironically, this bill was largely developed to target Uber/Lyft, demanding they treat drivers as employees rather than contractors. However, the ride-sharing industry was able to obtain an exemption.

So far, many truck drivers are protesting, but little concrete action has been taken. California has said that they will proceed with enforcement.

[RELATED: California Trucking Association tears down Solicitor General’s AB 5 argument]

Rarely mentioned is the fact these ports have long been recognized as some of the least productive ports in the world. World Bank evaluations of global ports have regularly scored the U.S. ports favorably. So, this isn’t a new development by any means.

UniBond has thankfully been able to avoid those ports for some years. Instead, we rely on the Vancouver, Canada port. From there, we send goods by rail through Canada and on to Detroit. This has the further benefit of avoiding rail congestion in Chicago (more on that later).

But Vancouver has had its own issues. First, volumes increased due to others avoiding California. Then the area was hit with flooding in November 2021, damaging key rail lines. The rail was quickly repaired. But, it is testimony to an “at capacity” situation that though traffic was restored by December, the backlogs still have not been totally cleared. Rail service delays have continued.

In previous years containers generally stayed in port for just 48 to 72 hours before going on outbound rail. Today the container dwell time — an industry expression for waiting — is averaging 5.5 days, according to the port authority.

East Coast ports expand their role

A natural response to the West Coast problems has been a movement from West Coast to East Coast U.S. ports. Now, with the California problems, ports in Houston, Savannah, Miami, and New York/New Jersey have grown in volumes.

To quote freight expert Descartes, "Volumes between West and East Coast ports shifted again in April 2022 compared to March 2022. Comparing the top five West Coast ports to the top five East Coast ports in April 2022 versus March 2022 shows that, of the total import container volume, the East increased to 45.4 percent of the total while the West represented 41.2 percent with all West Coast ports except Seattle combining to process 82,000 fewer containers. In March, the split was East Coast 41.4 percent and West Coast 45.0 percent."

[RELATED: As ocean freight prices and volume rise, shippers are struggling to keep up]

This is a great illustration of one of the challenges in understanding supply chain issues (or any complex system). For us normal human beings, these things are complex enough already. We often neglect to think through the likely consequences of change, or even understand a linkage when it occurs. This is particularly true when the cause and effect are separated by time, distance or both.

Ask yourself the question, “And what might that cause?” Well, in this case it’s reasonable to assume that most shippers from Asia will still need to get their goods here. So, it’s a fair bet that some of them will seek other ports that can substitute. Or, they may shift to different modes of transport. It has been reported that last year McDonalds sent potatoes from the U.S. to Japan by air. These had to be some costly fries! So, if you need to make decisions about these things, ask yourself that question, “And what might that cause?”

In a tightly knit system like shipping, you can be sure of one thing — it will have other consequences!

Panama Canal

With the increase in East Coast port activity, there’s naturally been a big impact on the Panama Canal. Several details about the canal are worth noting here.

First, despite multiple expansions over the years, the canal size remains a limit; the newest 'ultra large' container ships are too big to use it. (Though the actual demand for these may be limited, as East Coast ports also generally lack the ability to service these ships.) And, of course, using the canal takes time and money. The fees are relatively small — perhaps $75 per container on a typical ship. But the total time required may add one to two weeks to the vessel’s journey. An expensive proposition.

Turning to land transportation

Most important in intermodal container traffic are the railroads. While a small number of containers are shipped directly from port to destination by truck, the majority from major U.S. ports travel most of the way to their final destination by rail. With the modest improvements to the port capacity situation, we have had the unintended but natural consequence of shifting the “bubble” in capacity from the maritime sector to the rail system. Some critical points had already experienced major problems in 2021 — Chicago in particular.

These now have spread more generally. The Vancouver case has already been mentioned. More broadly, the Wall Street Journal reported in June rail backlogs were now at serious levels nationwide. A few specific examples include an accumulation of 29,000 containers in LA alone, a threefold increase over normal levels. Average wait time for May 2022 was 11.3 days. Chicago once again is a critical constraint for many West to East routes. Dwell time in Chicago is reported to have increased 20 percent over normal levels and that is only because many rail lines have delayed containers elsewhere.

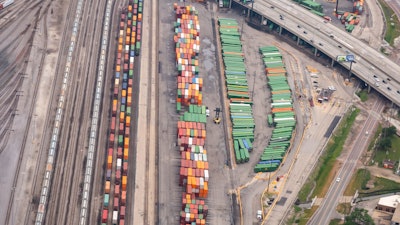

An aerial view of a crowded railyard in suburban Chicago. A key connection in coast-to-coast rail shipping, Chicago railyards have seen dwell times rise throughout the year.

An aerial view of a crowded railyard in suburban Chicago. A key connection in coast-to-coast rail shipping, Chicago railyards have seen dwell times rise throughout the year.

Yet another labor related 'wild card' is found in the rail situation. Rail workers also are working without an agreement. Here, too, a strike is possible in the future. In July, Federal mediators entered the talks which theoretically prohibits a strike for the moment.

Government responses

As has been already noted, most of the current supply chain constraints involve port infrastructure, followed by rail capacity. U.S. ports are locally run, though many enjoy some Federal funding. Some examples:

- Houston: A new container yard and a new wharf are in progress.

- Long Beach: Has announced a $1.5 billion upgrade to its rail system, but first stages won’t be complete until 2025 while the full project will need an additional ten years.

- Savannah: Has dredged its harbor to deepen by 15 percent (complete), and has launched a $128 million project to double rail intermodal capacity (which will take several years).

Wrapping it up

I wish I could be the bearer of good news, but this is the current state of the supply chain! The only other thing I can add is there’s no particular reason to expect conditions to improve in the near term. We just need to stay as flexible as we can, and deal with reality as we find it.

Best to all until next time!